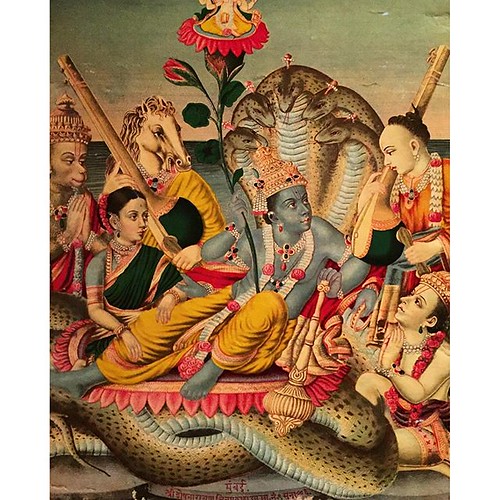

Narada Muni, son of Brahma, instructs his disciple Srila Vyasa, and requests him to write the Bhagavata Purana

It is said that Vedic injunctions are made large by the Puranas, or histories, since within these texts we can learn of how the Vedas have been implemented historically in the lives of humans, gods, sages and kings. By reading of the interplay of Vedic lore in the lives of real people we can be inspired to follow their example, and be warned of the consequences of acting in a manner contrary to Vedic dharma. Also written in the Puranas are descriptions of the compassionate, knowledge-giving actions of the many avatars of Sri Vishnu and the appearance of the Supreme Godhead, Sri Krishna.

The Puranas present selected events rather than a strict chronology. There are eighteen Puranas, notionally divided into three sections according to the predominating influence in the mind of the reader. The Puranas for those largely predominated by the influence of sattvika guna, or the ‘mode of goodness,’ for instance, will focus on Vishnu (Narayana), his incarnations and devotees. Other Puranas may focus on god Shiva or goddess Shakti.

Traditionally, there are five subjects of a Purana:

- Sarga or ‘Creation’

- Prati-Sarga or ‘Secondary Creation,’

- Vamsa or ‘Family Trees,’

- Manvantara or the ‘History of the Manus’ the creative gods, and finally

- Vamsa-anu-caritra, the details of the dynasties of kings and saints.

The Bhagavata Purana or Srimad Bhagavatam contains ten topics explained in 18,000 verses, a third of which describe the activities and speeches of Krishna. The verses are divided into 335 chapters, 90 of which are the tenth canto, the narrations of Krishna. According to a verse in the second canto of the book, the contents are as follows:

Śrī Śukadeva Gosvāmī said: In the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam there are ten divisions of statements regarding the following: the creation of the universe, subcreation, planetary systems, protection by the Lord, the creative impetus, the change of Manus, the science of God, returning home, back to Godhead, liberation, and the summum bonum. (Srimad Bhagavatam 2.10.1)

In his commentaries to the Chaitanya Caritamrita, the extensive biography of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, Srila Prabhupada writes:

These verses from Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam list the ten subject matters dealt with in the text of the Bhāgavatam. Of these, the tenth is the substance, and the other nine are categories derived from the substance. These ten subjects are listed as follows:

(1) Sarga: the first creation by Viṣṇu, the bringing forth of the five gross material elements, the five objects of sense perception, the ten senses, the mind, the intelligence, the false ego and the total material energy, or universal form.

(2) Visarga: the secondary creation, or the work of Brahmā in producing the moving and unmoving bodies in the universe (brahmāṇḍa).

(3) Sthāna: the maintenance of the universe by the Personality of Godhead, Viṣṇu. Viṣṇu’s function is more important and His glory greater than Brahmā’s and Lord Śiva’s, for although Brahmā is the creator and Lord Śiva the destroyer, Viṣṇu is the maintainer.

(4) Poṣaṇa: special care and protection for devotees by the Lord. As a king maintains his kingdom and subjects but nevertheless gives special attention to the members of his family, so the Personality of Godhead gives special care to His devotees who are souls completely surrendered to Him.

(5) Ūti: the urge for creation, or initiative power, that is the cause of all inventions, according to the necessities of time, space and objects.

(6) Manv-antara: the periods controlled by the Manus, who teach regulative principles for living beings who desire to achieve perfection in human life. The rules of Manu, as described in the Manu-saṁhitā, guide the way to such perfection.

(7) Īśānukathā: scriptural information regarding the Personality of Godhead, His incarnations on earth and the activities of His devotees. Scriptures dealing with these subjects are essential for progressive human life.

(8) Nirodha: the winding up of all energies employed in creation. Such potencies are emanations from the Personality of Godhead who eternally lies in the Kāraṇa Ocean. The cosmic creations, manifested with His breath, are again dissolved in due course.

(9) Mukti: liberation of the conditioned souls encaged by the gross and subtle coverings of body and mind. When freed from all material affection, the soul, giving up the gross and subtle material bodies, can attain the spiritual sky in his original spiritual body and engage in transcendental loving service to the Lord in Vaikuṇṭhaloka or Kṛṣṇaloka. When the soul is situated in his original constitutional position of existence, he is said to be liberated. It is possible to engage in transcendental loving service to the Lord and become jīvan-mukta, a liberated soul, even while in the material body.

(10) Āśraya: the Transcendence, the summum bonum, from whom everything emanates, upon whom everything rests, and in whom everything merges after annihilation. He is the source and support of all. The āśraya is also called the Supreme Brahman, as in the Vedānta-sūtra (athāto brahma jijñāsā, janmādy asya yataḥ (SB 1.1.1)). Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam especially describes this Supreme Brahman as the āśraya. Śrī Kṛṣṇa is this āśraya, and therefore the greatest necessity of life is to study the science of Kṛṣṇa.

Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam accepts Śrī Kṛṣṇa as the shelter of all manifestations because Lord Kṛṣṇa, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, is the ultimate source of everything, the supreme goal of all.

Two different principles are to be considered herein—namely āśraya, the object providing shelter, and āśrita, the dependents requiring shelter. The āśrita exist under the original principle, the āśraya. The first nine categories, described in the first nine cantos of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, from creation to liberation—including the puruṣa-avatāras, the incarnations, the marginal energy, or living entities, and the external energy, or material world—are all āśrita. The prayers of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, however, aim for the āśraya-tattva, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Śrī Kṛṣṇa. The great souls expert in describing Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam have very diligently delineated the other nine categories, sometimes by direct narrations and sometimes by indirect narrations such as stories. The real purpose of doing this is to know perfectly the Absolute Transcendence, Śrī Kṛṣṇa, for the entire creation, both material and spiritual, rests on the body of Śrī Kṛṣṇa.

Itihasas

The Sanskrit word Itihasa means ‘It happened thus’ and the texts are histories, normally written by an author who was contemporary with the events. The Mahabharata was written by Srila Vysadeva who witnessed many of the events described therein; and the Ramayana was composed by Sri Valmiki who was a contemporary of Sri Ramachandra. The Itihasas do not have to follow the structure of the Puranas, but they may also contain elements of the five subjects nonetheless. The Chandogya Upanisad (7.1.4) mentions the Puranas and Itihasas as the fifth Veda. The Bhagavata-Purana (1.4.20) also states, “The four divisions of the original sources of knowledge [the Vedas] were made separately. But the historical facts and authentic stories mentioned in the Puranas are called the fifth Veda.” Madhvacarya, commenting on the Vedanta-sutras (2.1.6), quotes the Bhavisya Purana, which states, “The Rig-veda, Yajur-veda, Sama-veda, Atharva-veda, Mahabharata, Pancharatra, and the original Ramayana are all considered Vedic literature. The Vaishnava supplements, the Puranas, are also Vedic literature.”

Bhagavad-gita

The Bhagavad-gita is a dialogue contained in the Shanti-Parva section of the Mahabharata, but the nature of the conversation ranges from Upanishadic verses through to the highest devotional theology. For this reason it is much loved and commonly known as Gita-Upanishad or Gitopanishad.

Since the times of Adi Sankaracarya in the early mediaeval period, it has been common for all schools of thought to establish their systems of philosophy on three texts, the Upanishads, the Vedanta Sutra and the Bhagavad-gita, collectively known as prasthana-trayi or the ‘three foundations’.